Over two dozen medical schools were founded in St. Louis during the 1800s. The heyday of the medical school craze in St. Louis was the 1890s, when 13 medical schools operated simultaneously within the city limits. In present-day St. Louis, only two medical schools remain in operation: those affiliated with Washington University and St. Louis University.

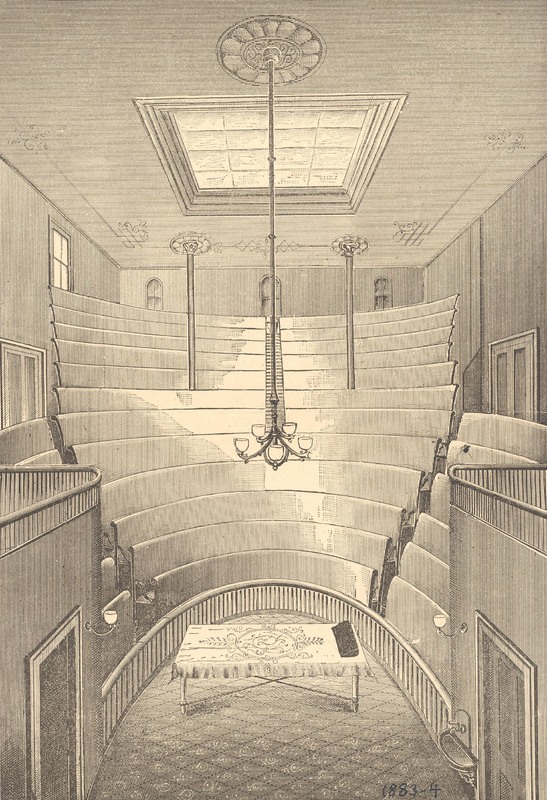

Nearly all of the 19th century medical schools in St. Louis operated as for-profit proprietary schools that received no local, state, or federal funding. Most medicals were owned and operated by their faculty members, which included ownership of the building and the equipment used in the affiliated hospitals of these schools as well. Any profits made by the schools or hospital clinics were divided amongst the owners.

Despite running these institutions as businesses, medical education and patient care was rarely a profitable enterprise. For this reason, there were generally no full-time teachers at these schools. Faculty members typically operated their own full-time private practice, and any revenue generated by class instruction served as supplemental income.

This operational design oftentimes led to poor educational outcomes, cutting corners in student instruction for the sake of cost savings, and limited investment in these schools in order to secure the most profit for the owners.

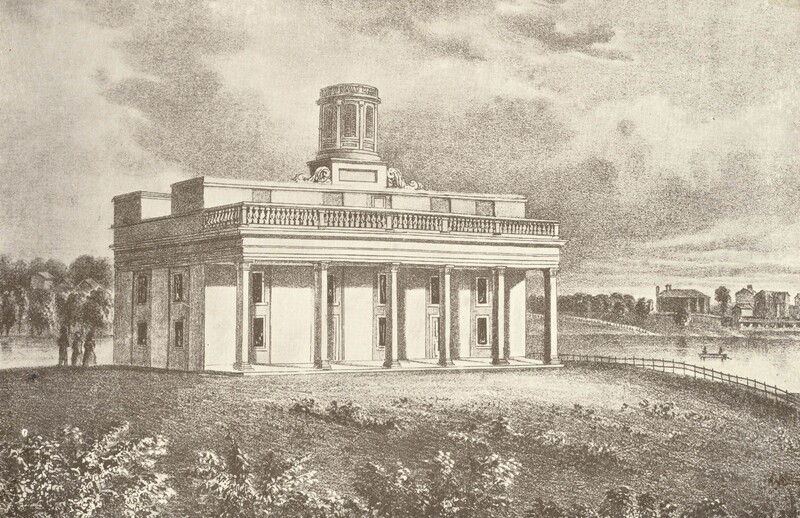

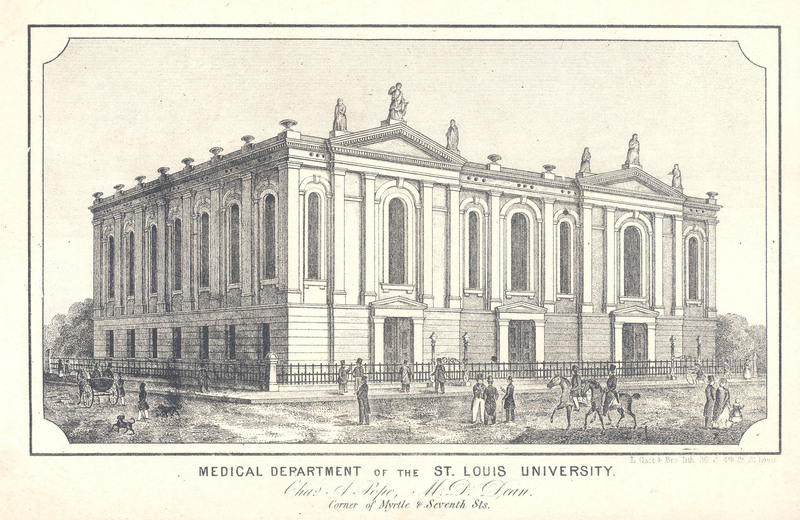

Although St. Louis University claims to have established the first medical school west of the Mississippi River, that honor belongs to the Medical Department of Kemper College. It is fair to say that St. Louis University attempted to establish the first medical school in Missouri after they received a charter from the state to do so in the 1830s. However, Kemper College is widely recognized as having the first medical school in operational existence west of the Mississippi River.

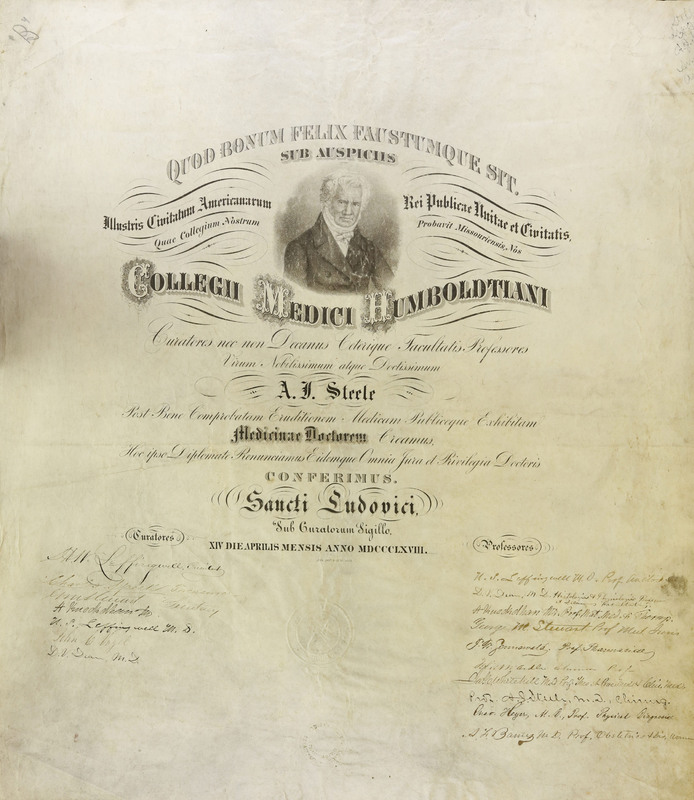

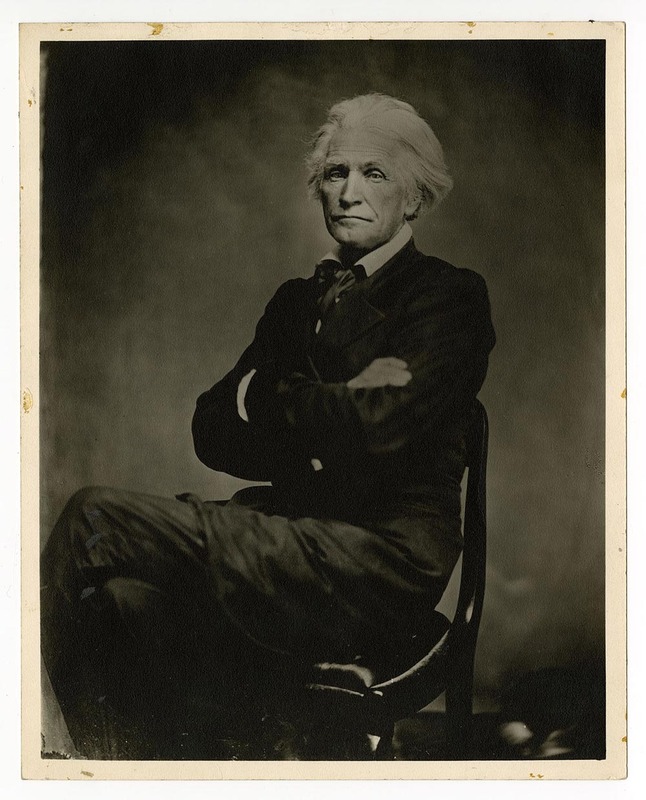

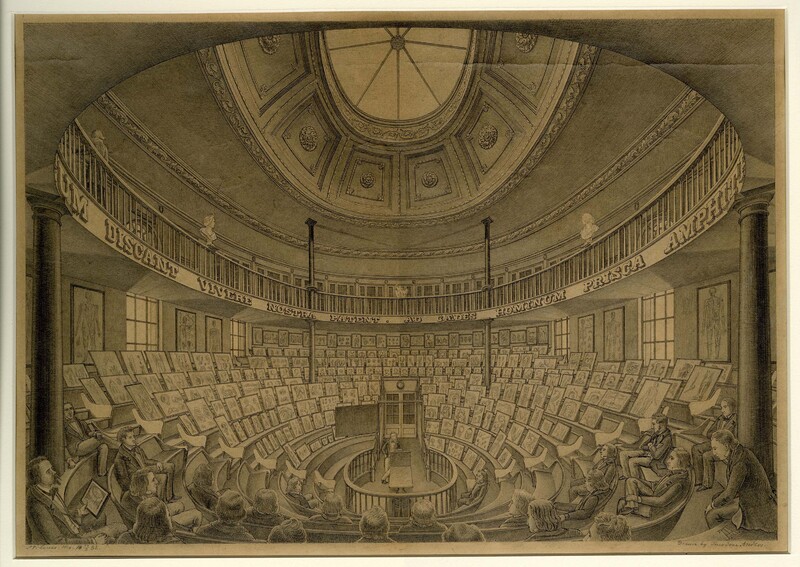

Joseph Nash McDowell established his medical school at Kemper College in 1840, and matriculated students into his school that same year. After many years of planning, St. Louis University began holding classes for medical students in 1842.

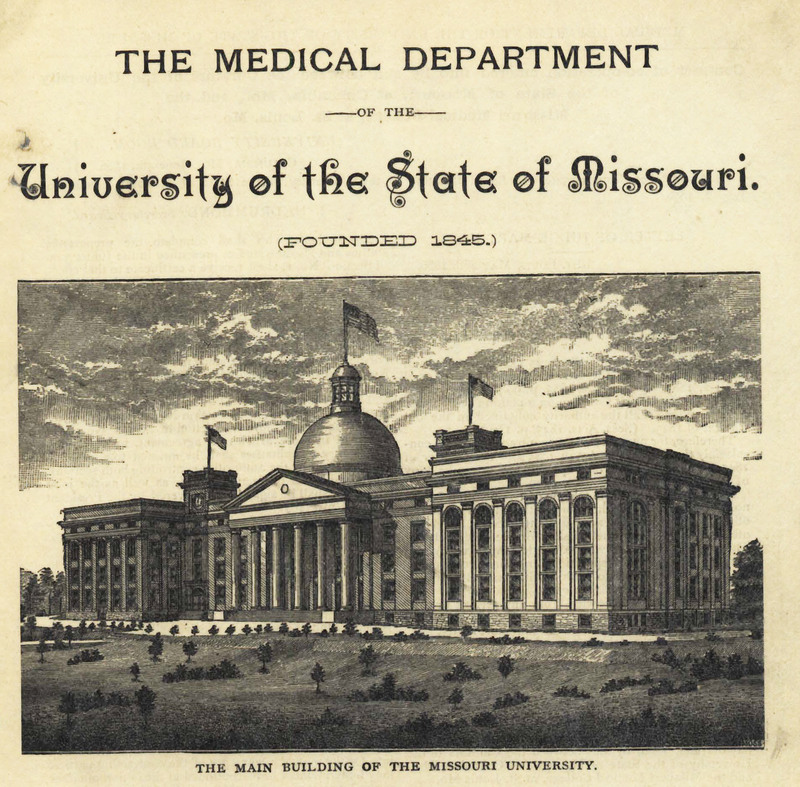

When Kemper College experienced financial troubles in the 1840s, McDowell aligned his medical school with University of Missouri in 1845. Medical school instruction, now loosely associated with the state’s only land grant school at the time, began the following year in the building Dr. McDowell personally owned and operated in St. Louis.

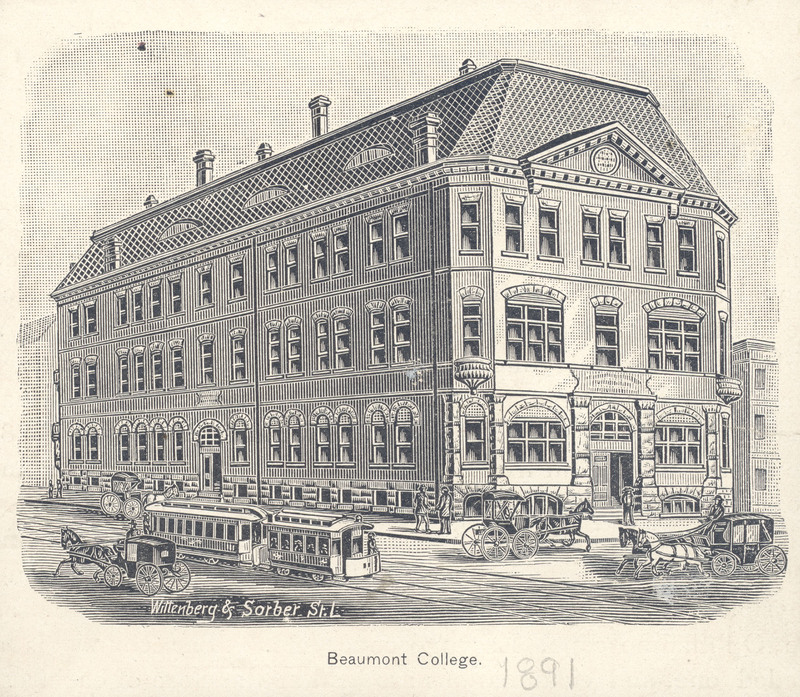

Although the main university campus was located in Columbia, Missouri, the University of Missouri’s medical school operated out of St. Louis from 1846-1857, and again from 1886-1890. See the section on Missouri Medical College for further explanation.

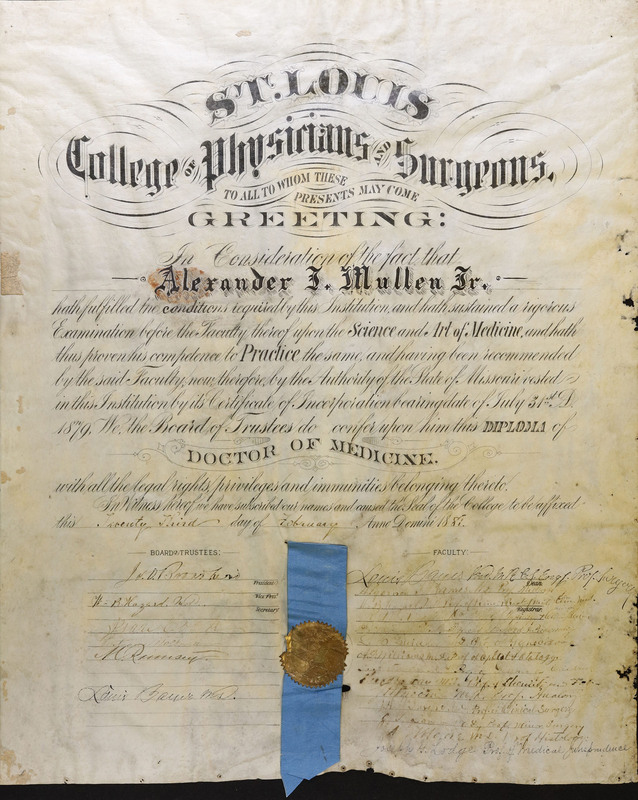

The faculty of the Medical Department at St. Louis University, who were operating the school under the proprietorship model, dropped the affiliation with the university in 1855 when they secured an independent charter from the state’s General Assembly to establish the St. Louis Medical College.

The reason for removing the school’s affiliation to St. Louis University has been credited to the Know Nothing movement in the mid-1850s, which launched a violent xenophobic campaign throughout the United States. The Know Nothings were especially prevalent in the immigrant-rich city of St. Louis.

Viewed as welcoming to the city’s large contingent of Catholic immigrants from Germany and Ireland, St. Louis University was targeted in several disastrous riots perpetrated by the Know Nothings, one of which resulted in the near total destruction of the medical school. It has been speculated that the medical school faculty sought to disassociate their school from St. Louis University to avoid further xenophobic mob attacks.

Prior to moving to St. Louis in 1839, Dr. Joseph Nash McDowell served as an anatomy professor at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and at the Medical Department of Cincinnati in Ohio. He founded the medical department at Kemper College in St. Louis in 1840, and then realigned the department with the University of Missouri in 1846.

Just as he had cut ties with Kemper College to overcome financial hardships, McDowell was forced to disassociate his school with the University of Missouri in 1857 for the same reason. This action left the state school without a medical department for several decades.

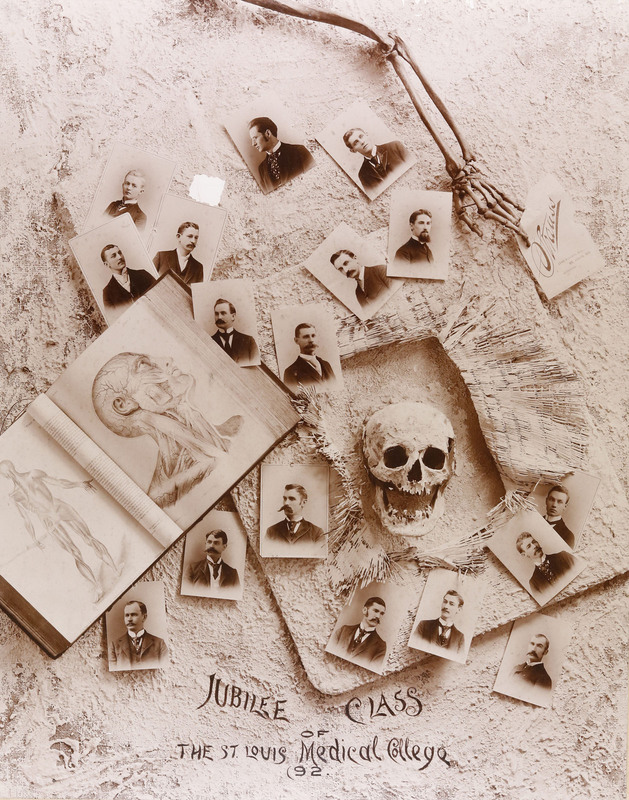

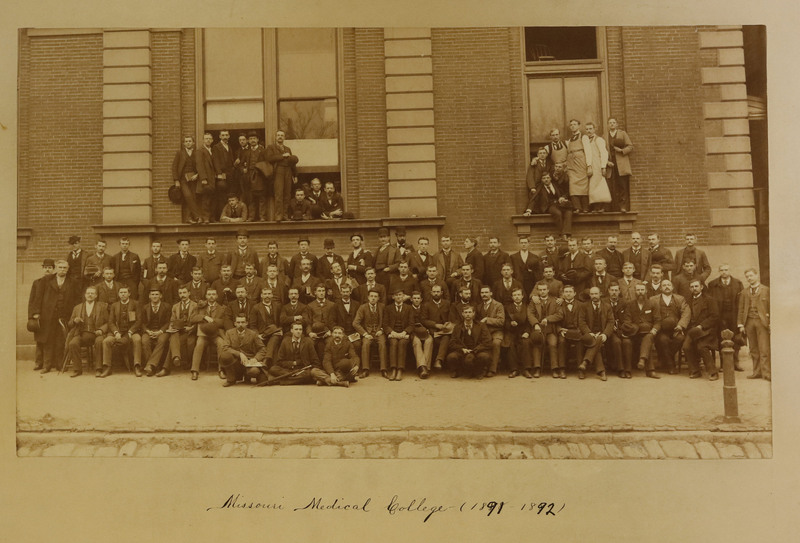

McDowell established the independent Missouri Medical College in 1857, and served as its Dean until his death in 1868. Peculiarly, the Missouri Medical College reaffirmed its affiliation with the University of Missouri in 1886, but this union only lasted four years when this persnickety medical school became an independent entity once again in 1890. After becoming independent a second time, the school once again adopted its former name, the Missouri Medical College, until it folded into Washington University in 1899.

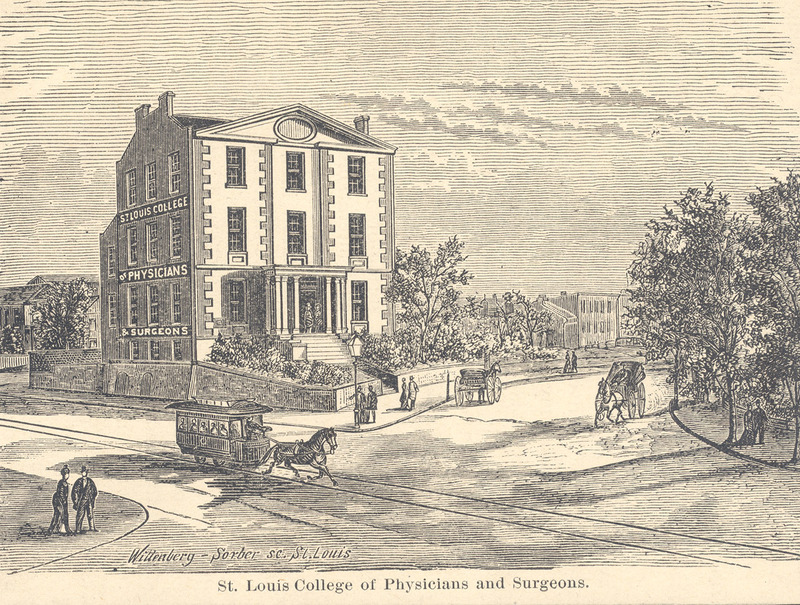

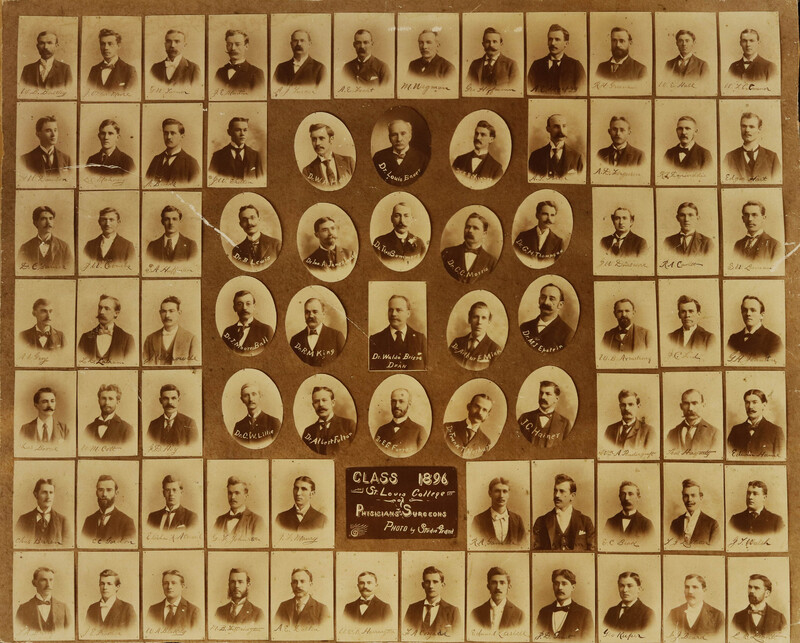

Many of the schools featured in this exhibit would be considered “diploma mills” by modern standards. One of the most egregious examples, the St. Louis College of Physicians and Surgeons, was featured in an expose by the St. Louis Star newspaper on October 15, 1923.

In this piece that made worldwide headlines, Dean Waldo Briggs was accused of -- and he later confessed to -- providing advance copies of licensing exam questions to students, lax proctoring of classes, and performing informal oral examinations. He also intentionally guiding diploma purchasers (that he comically referred to as dumb bells) to corrupt licensing officials in Arkansas and Connecticut.

From the St. Louis Star newspaper, October 15, 1923:

I was a resident of St. Louis. I was interested in studying medicine by a man who was then passing through the mill. He introduced me to Dr. Waldo Briggs, dean of the St. Louis College of Physicians and Surgeons. I told Dr. Briggs that I wanted to become a doctor, but could not go to school for four years. He said he would get me out in two. I told Dr. Briggs that I did not have a high school diploma, and he said he would fix me up. He told me it would not be necessary to buy credentials showing that I had attended classes in a medical school for the freshman and sophomore years. Instead, he said, he would insert my name in the class records for those years, and I could begin as a junior. He said he would arrange to get me a high school paper. A few days later Prof. William P. Sachs came to the school and told me he had a high school certificate made out for me. I paid him $25 for it and turned it over to Dr. Briggs. I had no money to pay for my tuition, and Dr. Briggs agreed that I could repay him for supplying the freshman and sophomore year credits by taking care of his books, which I did.

*Unnamed source to St. Louis Star reporter who had obtained a medical diploma from the St. Louis College of Physicians and Surgeons. The above account was reprinted in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 81, Issue 19, page 1631.

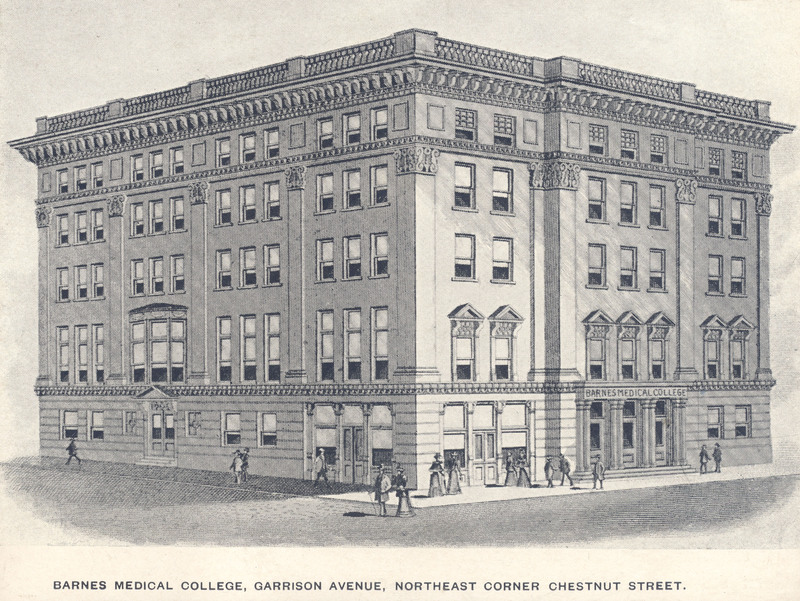

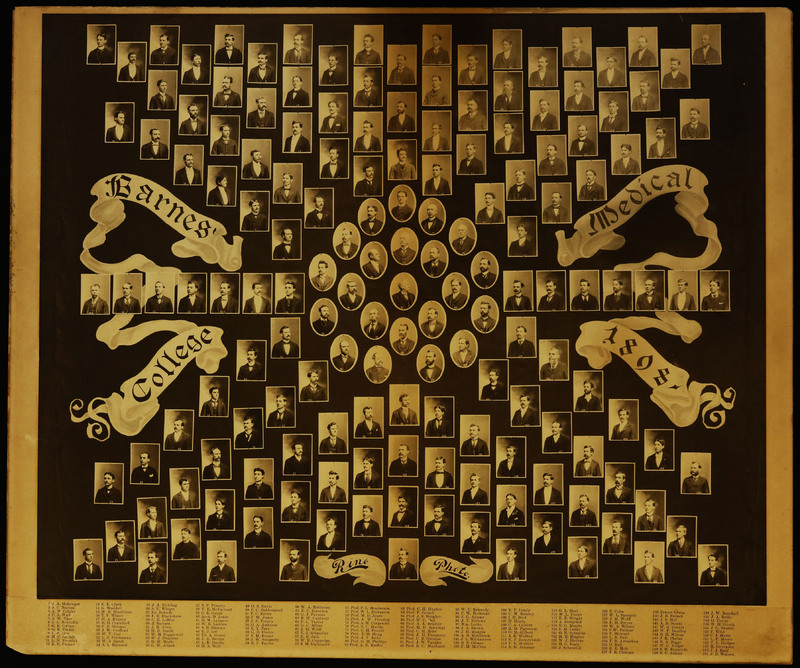

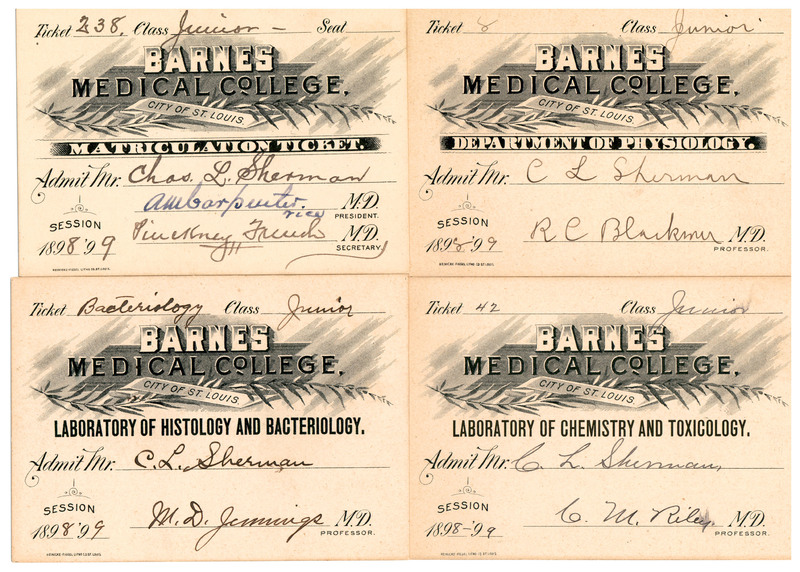

Robert Barnes was a very wealthy St. Louis merchant and banker who left $250,000 of his estate for the construction of a new hospital for the city. By no coincidence, Barnes Medical College was founded in the same year as his death in 1892. The college administrators named their medical school after Mr. Barnes in hopes of securing the funding for the construction of a hospital to attach to their new classroom building. This plan did not materialize.

Despite the failed effort to acquire funds from the Barnes estate, Barnes Medical College flourished as one of the largest degree granting medical schools in the country by the end of the 1800s. The institution also operated a dental college, a college of pharmacy, and a nurses’ training program in addition to its large medical school. However, the school very quickly became under financial duress in the early 1900s. Barnes Medical College united with American Medical College in 1912 to become National University. The St. Louis College of Physician and Surgeons also merged with this group in 1915. The school collapsed despite these mergers, and the last medical students graduated in 1918.

In hindsight, the trustees of the Robert Barnes estate made a wise decision to pass on investing in this soon-to-fail medical school and instead grew the estate through extraordinarily successful investments. These profitable speculations amounted to over one million dollars in the next 20 years, which enabled the construction of a state-of-the-art hospital that opened in 1914. This hospital, which has been consistently deemed one of the best in the United States for the past century, continues to operate under the name as Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

It would be an understatement to classify the quality of 19th century medical education in the United States as irresponsibly poor. Loosely drawn educational chartering laws in most states allowed schools to issue diplomas on the basis of minimal or no legitimate educational experience.

Entrance requirements for medical schools, most of them only two-year programs, were absurdly low. There was no MCAT-equivalent test for prospective medical students. A bachelor’s degree or high school diploma was not required for admittance into most medical schools. Passing a meager admittance test would suffice to qualify for admission for many medical schools.

In fairness, most 19th century medical schools were not founded with the intention of serving as diploma mills. Many of the schools were originally founded with the legitimate purpose of providing quality education to their students. Nevertheless, nearly all medical schools in the 19th century struggled financially.

Many of the 19th century medical schools of St. Louis were in existence for less than 10 years. When they came under financial duress, some schools began admitting hundreds of students each semester -- many of them wholly unqualified for medical practice -- in order to generate funding to keep the school in operation. One such school, Barnes Medical College, became the largest of all the schools in St. Louis when it enrolled over 600 students at the turn of the century.

The infamous Flexner Report on medical education in North America published in 1910 served as the death knell for all struggling medical schools, especially those schools that had yet to affiliate with a reputable university that were still operating on the proprietary model. Abraham Flexner famously referred to Washington University’s medical school as “a little better than the rest I have seen elsewhere, but absolutely inadequate in every essential respect”. Flexner’s harsh criticism of WU’s medical school led to the complete reorganization of the school, which included a new Dean, all new department heads, and a brand new medical campus (our current location) that opened in 1915.